-

Publish Your Research/Review Articles in our High Quality Journal for just USD $99*+Taxes( *T&C Apply)

Offer Ends On

Philip L Millstein*, Carlos Eduardo Sabrosa and Wai Yung

Corresponding Author: Philip L Millstein, Department of Restorative Dentistry, Harvard School of Dental Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Received: January 3, 2026 ; Revised: January 4, 2026 ; Accepted: January 6, 2026 ; Available Online: January 8, 2026

Citation: Millstein PL, Sabrosa CE & Yung W. (2026) The Intensity of Occlusal Contact Patterns Reflects a Damaging Pattern of Wear. J Oral Health Dent Res, 5(2): 1-4.

Copyrights: ©2026 Millstein PL, Sabrosa CE & Yung W. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Views & Citations

Likes & Shares

This paper describes a method to gather numerical data that can be used to print occlusal profiles on therapeutic bite guards.

Keywords: occlusion, imaging, bruxing, printing, bite guard.

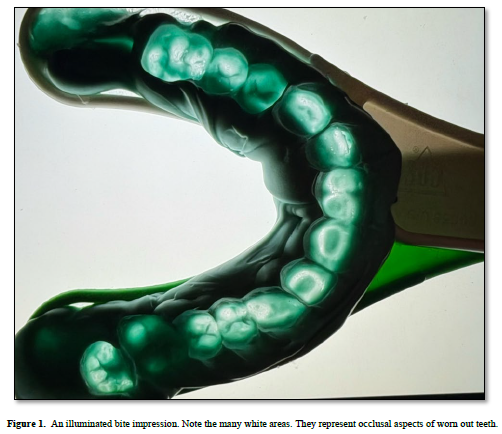

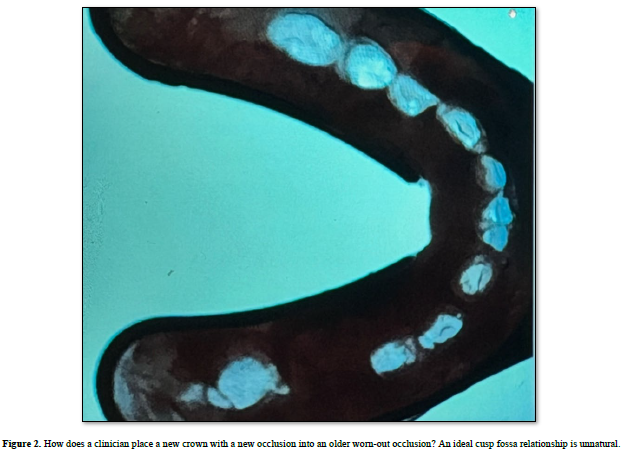

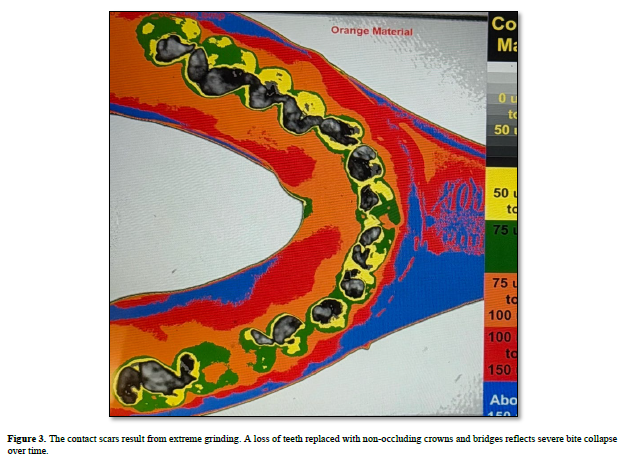

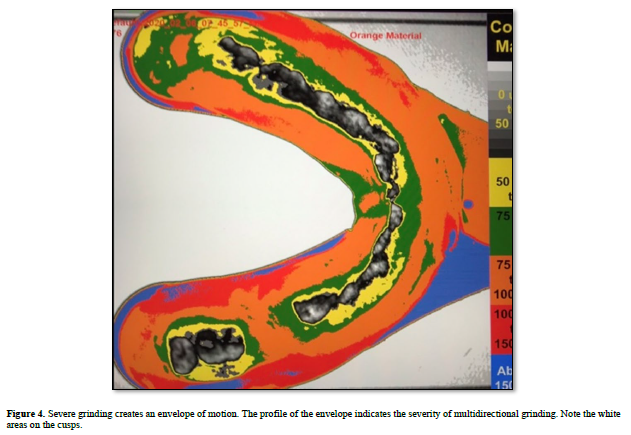

Listen to the rhythm of the falling rain; and the pitter patter of the rain drops. (1). Listen to the rhythm of the grinding teeth and the bruxing of the broken teeth. Watch the sliding jaws as they pass by-one another in a chopping motion (2). This is a rhythm that beats to its own tune. Remove one or more teeth and the oral environment is forever changed. A rehabilitation can be clinically constructed and the rhythm of occlusion reconstituted but only if the occluding teeth synchronize with one another. Ill-fitting crowns with no fit occlusions are detrimental to the dentition (3). The complexities of brain-body interactions are unknown (4). Body-brain communications may indicate ways to treat bruxism. Bite patterns are scratched and ground into the occlusal surfaces of bite guards. The patterns differ for each person. We may alter rhythms of articulation using bite splints but we can’t cure severe grinding. When we make a bite -guard the patient scratches and grinds their occlusion into the biting surface. We do not take into consideration the bite force, hardness of the appliance, rhythm, fit, thickness and vertical dimension. If a therapeutic occlusion was designed, printed and cut into the biting surface of a printed guard the internal rhythm which projects force may be less damaging. Occlusal contacts make contact upon closure; the rhythm of closure drives the contacts into position (5). You cannot stop the rhythm but you can work towards altering the contact patterns by using therapeutically designed bite guards. The information for designing the personalized bite guards comes from a triple tray occlusal impression. (6). Standard bite guards block full closure; therapeutic guards block full closure but are also used to treat contact disfunction. We can either print the patient’s existing occlusion or we can create a therapeutic bite design and print it into the biting surface. It is now personalized. We can replace the guard at frequent intervals. The guard is used as a therapeutic device which is prescription driven. The bite must be rehabilitated before repairing it (7). All the information for printing the bite into guard is in the inter occlusal recording but it must be interpreted and coded. An invisible envelope of motion forms upon grinding which can be seen and evaluated using the scan. The intense areas of contact seen in the envelope may indicate a chopping motion related to muscle strength and contraction. The flow properties of the impression material allow us to record tooth contact and associated grinding movements in a closed environment (8). The wear from grinding breaks down the occlusal contact surfaces. An accurate impression is taken using a triple tray loaded with a non-set silicone impression material. The bite impression (Figure 1) is centered on an activated light box which is positioned vertically at a fixed distance from a recording camera which is connected to an image analysis (Image J) program linked to a computer. Readings are made on the computer screen (6). The information is processed to measure occlusal contact position, surface area, and contact intensity (Figure 2). The size and area of the ground envelope of motion is made visible along with the patterns of occlusal contact (Figure 3). Grinding and bruxing actions are analyzed. (Figure 4). It is one thing to cite findings concerning occlusal profiles but it is another thing to do something with the findings. Most occlusal pathologies are overlooked until the damage is no longer repairable. The information for early treatment is recorded in the impression. Gathering the information requires clinical expertise. Analyzing the findings is the responsibility of the dentist. As always diagnosis and treatment planning lead to smart treatment.

No Files Found

Share Your Publication :